Subjecting 100,000 Americans, including children, to electroshock (ECT) constitutes torture, given the risks associated with it, CCHR says.

Subjecting 100,000 Americans, including children, to electroshock (ECT) constitutes torture, given the risks associated with it, CCHR says.

The Citizens Commission on Human Rights International (CCHR), a non-profit organization dedicated to protecting human rights in the field of mental health, is raising alarm over the dangers associated with Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT), commonly known as electroshock. The organization is once again advocating for a ban on this controversial practice, highlighting the potential risks, including memory loss and brain damage. Psychiatrists estimate 100,000 Americans are given ECT every year, but there are no formal records kept on its use, despite its inherent risks. Through Freedom of Information Act requests, CCHR has established that teenagers and children ages 5 or younger have also been exposed to it, constituting, as the United Nations says, an act of torture.

The renewed call for a ban comes in response to the first-ever international survey of people who have undergone ECT, conducted by a team of researchers including individuals from England, Northern Ireland, and the United States. The survey is also distinctive as it simultaneously includes input from relatives and friends of ECT recipients.

The research team, consisting of five co-researchers, three of whom have personally experienced ECT, has launched a comprehensive survey.[1]

Historically, ECT research has been criticized for relying heavily on the subjective opinions of prescribing psychiatrists, leading to generally favorable outcomes. However, smaller studies in the 1980s and 1990s, which directly asked ECT patients about their experiences, revealed less favorable outcomes, including rates of permanent memory loss.[2]

While the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has permitted ECT devices to remain on the market, it also cautions that “Long-term safety and effectiveness of ECT treatment has not been demonstrated.”[3] In 1976, the devices were grandfathered in, and subsequently, no clinical trials have proven their safety and efficacy.

Lisa Morrison, a co-researcher based in Belfast, Ireland, expressed concern about the treatment’s impact on memory, stating, “ECT has caused huge gaps in my memory. It’s particularly distressing as a Mum to have lost significant memories of my children growing up…. The treatment can sometimes affect relatives too and their relationship with those receiving it. We want everybody to know their experiences matter.”

CCHR played a pivotal role in securing the first legislative safeguards against ECT use, a landmark achievement dating back to the 1970s. The organization also contributed to the prohibition of electroshock therapy for minors in California and subsequently in various other states, including Texas and in Western Australia.

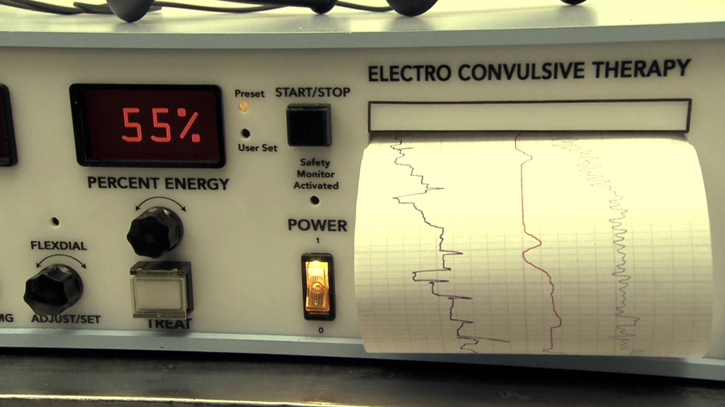

ECT sends up to 460 volts of electricity through the brain to induce a grand mal seizure, which induces a loss of consciousness and violent muscle contractions, masked by an anesthetic.[4]

Recent guidance from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) on Mental Health, Human Rights, and Legislation, also asserts that ECT can result in brain damage. This requirement is supported by information found in a manual from a U.S. electroshock device manufacturer, which confirms the occurrence of this adverse effect.[5]

The online, anonymous survey, approved by the University of East London Ethics Committee, is open to individuals worldwide who are at least 18 years old and have undergone ECT in the past, excluding the last four weeks.[6]

In the UK, it has been reported that around 40% of ECT procedures are non-consensual and performed on individuals detained against their will under the framework of the UK Mental Health Act.[7] In the United States, numerous states permit involuntary ECT, even though the United Nations Convention against Torture explicitly denounces such practices.[8]

In 2013 the UN Committee against Torture stated that when forcibly given or administered without a patient’s consent, electroshock constitutes torture—a practice that needs to be outlawed.[9]

So detrimental are its effects that CCHR produced a definitive documentary on electroshock, Therapy or Torture: The Truth About Electroshock.

CCHR urges those who have undergone ECT or have close connections to ECT recipients to participate in the survey, emphasizing the importance of hearing the voices of those directly affected by this controversial treatment. It also asks for people to support its online petition calling for a ban on ECT.

[1] John Read, “International Survey of Electroconvulsive Therapy,” Psychology Today, 29 Jan. 2024, https://www.psychologytoday.com/nz/blog/psychiatry-through-the-looking-glass/202401/international-survey-of-electroconvulsive-therapy

[2] Ibid.

[3] https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/12/26/2018-27809/neurological-devices-reclassification-of-electroconvulsive-therapy-devices-effective-date-of, under Response 23, “Response” 4; § 882.5940 Electroconvulsive therapy device, (J)

[4] https://www.cchrint.org/2023/11/03/patients-given-electroshock-brain-damage-recourse/

[5] https://www.cchrint.org/2023/09/18/who-guideline-condemns-coercive-psychiatric-practices/ citing World Health Organization, OHCHR, “Guidance on Mental Health, Human Rights and Legislation,” 9 Oct. 2023, p. 58

[6] Op. cit., Psychology Today, 29 Jan. 2024

[7] https://www.mentalhealthtoday.co.uk/news/in-our-right-mind/exclusive-crisis-care-faces-legal-fall-out-after-nhs-digital-lose-control-of-non-consensual-ect-data

[8] https://jaapl.org/content/51/1/47; “Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, Juan E. Méndez,” UN Human Rights Council, 1 Feb. 2013, http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/RegularSession/Session22/A.HRC.22.53_English.pdf; https://www.cchrint.org/memorandum-need-for-human-rights-in-mental-health-laws/

[9] Ibid., Juan E. Méndez,” United Nations, General Assembly, Human Rights Council, 1 Feb. 2013, p. 21, para 85